First Brands' Bankruptcy: What This Collapse Teaches Us About Building the Future

It’s not often you see a ghost. But on October 5, 2025, the entire financial world saw one. It wasn't a spectral apparition; it was the bankruptcy filing of First Brands Group, a company that, on paper, looked like a pillar of the American automotive aftermarket. We’re talking about names you know, names you’ve probably trusted in your own car—Fram filters, Trico wipers, Carter fuel pumps. These aren’t ephemeral tech startups; they’re tangible, cash-generating businesses.

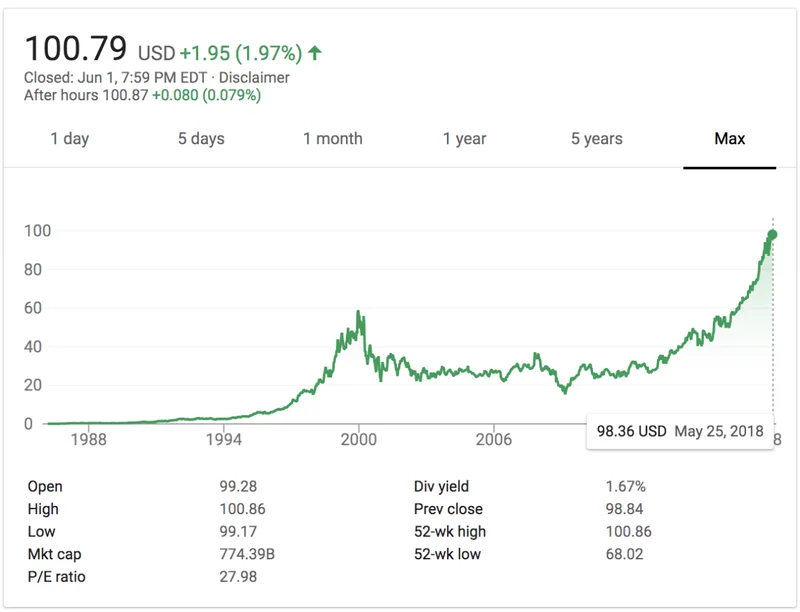

And yet, in the span of just 15 trading days, the value of its debt didn't just dip; it fell off a cliff. Imagine watching a stock ticker, but instead of a gentle slope, it’s a sheer, terrifying drop. A loan trading near its full value one month is suddenly worth less than a third of that just a few weeks later. This wasn't a slow decline; it was a catastrophic systems failure, a sudden, shocking collapse that left seasoned fund managers reeling (The Funds Most Affected by First Brands’ Bankruptcy and What Investors Can Learn From Them) and asking a single, vital question: What did we miss?

The easy answer, the one you’ll read in most financial post-mortems, is about position sizing and diversification. And yes, that’s true. It’s sound advice. But it’s also profoundly unsatisfying because it only addresses the symptom, not the disease. When I first dug into the filings and saw the layers of hidden leverage, I honestly felt a chill—it's the kind of elegant, terrifying complexity that signals a deeply broken system. The real story here isn’t about a few funds that bet too big on the wrong horse. It’s about the ghost in the machine of modern finance.

The Financial Dark Matter

On the surface, First Brands looked like a standard case of a highly leveraged company. At the end of 2024, it was carrying about $6.1 billion in debt against $1.1 billion in earnings. That’s a leverage ratio of over 5-to-1, which is aggressive, certainly, but not an alien lifeform in the world of below-investment-grade debt. Plenty of companies operate in that zone. It was the known risk, the calculated gamble that fund managers get paid to assess.

The real problem was what you couldn't see. The killer wasn’t the debt on the balance sheet; it was the debt lurking in the shadows. First Brands was a master of what’s known as "working-capital finance maneuvers"—in simpler terms, it was a series of incredibly complex and opaque ways to get cash now by mortgaging its future. This included selling off customer invoices for immediate payment, having lenders pay their suppliers directly, and even borrowing against the very goods sitting unsold in their warehouses.

This is the financial equivalent of dark matter. In astrophysics, we know dark matter exists because we can see its immense gravitational pull on the stars and galaxies we can see, even though we can't observe the substance itself. In the same way, First Brands had this massive, invisible financial structure pulling and warping its corporate reality. The on-the-books debt was the visible galaxy, but the off-the-books maneuvers were the unseen mass, and its gravitational force is what ultimately caused the entire system to collapse into a black hole.

This wasn't just an accounting trick; it was a fundamental information failure. The company’s disclosures were so opaque that when it finally needed help from its lenders in September, they took one look at the tangled mess and refused to play ball. They couldn't see the bottom. And in finance, when you can't see the bottom, you assume it's a bottomless pit. So, my question is this: How many other companies are operating with this kind of financial dark matter on their books? Is First Brands a singular, spectacular failure, or is it the first tremor of a much larger, systemic earthquake we’re not prepared for?

Building a Digital Immune System

The collapse of First Brands is a stark reminder that we are running 21st-century financial markets on a 20th-century information architecture. The idea that we still rely on quarterly reports and dense, legalese-filled disclosures to understand a company's health is, frankly, archaic. It’s like trying to navigate a supersonic jet with a paper map and a compass. We need a fundamental upgrade. We need to build a digital immune system for our economy.

What does that look like? Imagine a world where corporate finance isn’t a black box, opened only four times a year. Imagine a system built on radical transparency, where major financial commitments—even the complex off-balance-sheet ones—are recorded on an immutable, transparent ledger in near real-time. This isn’t a science-fiction fantasy; the foundational technologies, like blockchain and distributed ledgers, already exist. The speed at which this data could be processed and analyzed by AI is just staggering—it means the gap between a company's action and the market's knowledge of that action could shrink from months to minutes, preventing these hidden risks from ever festering into system-shattering crises.

This is the kind of breakthrough that reminds me why I got into this field in the first place. We could deploy AI-powered auditors that don't just check the boxes but actively hunt for anomalies, sniffing out the tell-tale patterns of these "dark matter" financing schemes before they reach critical mass. These systems wouldn't just be about catching bad actors; they'd be about creating an environment where this level of opacity is simply impossible.

Of course, with this kind of power comes immense responsibility. We can’t just build a panopticon for corporate surveillance. The goal must be to create a system that fosters trust, stability, and genuine value creation, not just a more efficient tool for speculation. The ethical framework we build around this technology will be just as important as the code itself. But the alternative—to keep flying blind and just hope we miss the next iceberg—is no longer acceptable. What does it say about our system when a company with household brands can simply dissolve into a mist of financial engineering?

This Isn't About Debt; It's About Data

In the end, the lesson from the First Brands implosion isn’t just "diversify your portfolio." That’s a coping mechanism, not a solution. The real, urgent lesson is that we have a catastrophic data problem. The bankruptcy wasn't a failure of a single company; it was a failure of an information ecosystem that allowed fatal risks to remain invisible until it was far too late. The future of a stable, resilient economy won't be secured by simply hiring smarter fund managers. It will be secured by building smarter, more transparent systems. The most important investment we can make right now isn't in a particular stock or bond—it's in an architecture of truth.

-

The Business of Plasma Donation: How the Process Works and Who the Key Players Are

Theterm"plasma"suffersfromas...

-

ASML's Future: The 2026 Vision and Why Its Next Breakthrough Changes Everything

ASMLIsn'tJustaStock,It'sthe...

-

Morgan Stanley's Q3 Earnings Beat: What This Signals for Tech & the Future of Investing

It’seasytoglanceataheadline...

-

The Manyu Phenomenon: What Connects the Viral Crypto, the Tennis Star, and the Anime Legend

It’seasytodismisssportsasmer...

-

The Nebius AI Breakthrough: Why This Changes Everything

It’snotoftenthatatypo—oratl...

- Search

- Recently Published

-

- Misleading Billions: The Truth About DeFi TVL - DeFi Reacts

- Secure Crypto: Unlock True Ownership - Reddit's HODL Guide

- Altcoin Season is "here.": What's *really* fueling the latest altcoin hype (and who benefits)?

- The Week's Pivotal Blockchain Moments: Unpacking the breakthroughs and their visionary future

- DeFi Token Performance Post-October Crash: What *actual* investors are doing and the brutal 2025 forecast

- Monad: A Deep Dive into its Potential and Price Trajectory – What Reddit is Saying

- MSTR Stock: Is This Bitcoin's Future on the Public Market?

- OpenAI News Today: Their 'Breakthroughs' vs. The Broken Reality

- Medicare 2026 Premium Surge: What We Know and Why It Matters

- Accenture: What it *really* is, its stock, and the AI game – What Reddit is Saying

- Tag list

-

- Blockchain (11)

- Decentralization (5)

- Smart Contracts (4)

- Cryptocurrency (26)

- DeFi (5)

- Bitcoin (30)

- Trump (5)

- Ethereum (8)

- Pudgy Penguins (5)

- NFT (5)

- Solana (5)

- cryptocurrency (6)

- XRP (3)

- Airdrop (3)

- MicroStrategy (3)

- Plasma (4)

- Zcash (7)

- Aster (10)

- qs stock (3)

- mstr stock (3)

- asts stock (3)

- investment advisor (4)

- morgan stanley (3)

- ChainOpera AI (4)

- federal reserve news today (4)