China's Rare Earth Mineral Export Controls: What the Data Says About Market Impact and Geopolitical Risk

China's Rare Earth Gambit: It's Not a Threat, It's a Timetable

On Thursday, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce made a move that was as predictable as it was potent. The announcement to tighten export controls on a dozen rare-earth metals wasn’t a shock to anyone who tracks supply chain data, but the timing and specificity of the action reveal a clear, calculated strategy. This isn't a sudden fit of pique; it's a precisely calibrated move on the global chessboard ahead of critical trade talks.

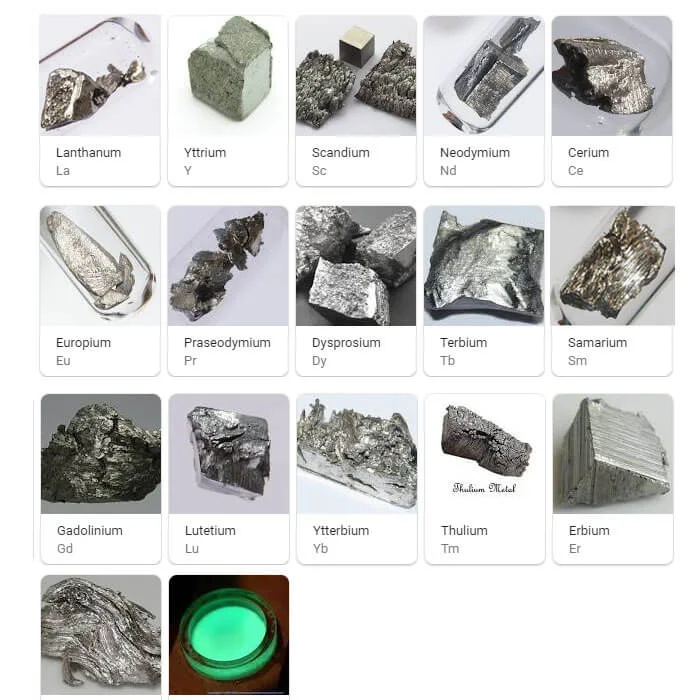

Beijing’s official reasoning cites “national security interests,” a familiar and conveniently opaque justification. The Ministry of Commerce claims certain foreign entities are diverting these materials for military applications, posing a threat to global stability. While plausible on its face, the data suggests a more immediate and pragmatic motive. The restrictions, which add five more metals to an existing list (holmium, erbium, thulium, europium and ytterbium), are set to take effect on December 1, 2025.

This date is not arbitrary. It creates a roughly two-and-a-half-month window of escalating pressure, perfectly bracketing the upcoming APEC summit where President Trump and President Xi are expected to meet. The message is unambiguous: the clock is ticking. For years, the world has operated on the assumption of China as a reliable, low-cost supplier. That assumption is now being deliberately and methodically dismantled as a tool of statecraft.

Deconstructing the Chokepoint

To understand the leverage Beijing now wields, you have to look past the mining figures and focus on the processing data. While China mines approximately 60% of the world's rare earths, it processes a staggering 90%. This is the critical chokepoint. Owning the crude oil is one thing. Owning the only refinery on the planet that can turn it into gasoline is something else entirely. China doesn't just dig the ore out of the ground; it controls the complex, dirty, and technologically intensive process of separating these 17 chemically similar elements into usable materials.

And this is the part of the announcement that I find particularly telling. Beijing didn't just restrict the metals; they also placed restrictions on the export of the specialist technology used to refine them. It's a move designed not just to limit the current supply, but to actively prevent other nations from building a competing supply chain. It's a strategic moat-digging exercise in real time.

The dependency this creates for the United States is stark. According to the US Geological Survey, America sourced 70% of its rare earth compounds and metals from China between 2020 and 2023. These aren't materials for consumer trinkets. They are fundamental inputs for high-end defense manufacturing: F-35 fighter jets, Tomahawk missiles, and advanced radar systems. The Pentagon runs on these elements. Gracelin Baskaran at CSIS correctly identifies that this move will "deepen these vulnerabilities" for the U.S. defense industrial base at a moment of rising tension.

China now has export restrictions on about two-thirds of all rare earth metals—to be more exact, 12 of the 17. The requirement for foreign companies to obtain special licenses, detailing the end-use of the product, effectively gives Beijing veto power over segments of its customers' manufacturing operations. This isn't a free market anymore; it's a managed one, where access is contingent on alignment with Chinese strategic interests.

The Art of the Deadline

The brilliance of this maneuver lies not in its power, but in its timing. By setting the effective date for December 1st, China has created an explicit deadline for negotiation. It transforms an abstract threat into a concrete event with a countdown. Every day that passes without a deal increases the pressure on Western procurement officers and defense contractors. It forces the issue.

This raises a critical question the official statements don't answer: What specific concessions is Beijing targeting with this deadline? Is this merely a bargaining chip to roll back the 30% US tariffs that remain from the trade war, or is it a strategic countermove aimed at forcing a relaxation of Washington's own semiconductor export controls? Given that rare earths are essential for semiconductor manufacturing, the symmetry is hard to ignore.

The U.S. restricted China's access to high-end chips in 2022, aiming to kneecap its technological advancement. Now, China is restricting the foundational materials needed for America's most advanced military and technological hardware. It’s a classic case of asymmetrical warfare, fought not with missiles but with bills of lading and export permits. Each side has identified and is squeezing the other's most vulnerable supply chain chokepoint.

The next two months will be telling. We'll see frantic calls from industry lobbyists, urgent meetings at the Pentagon, and a flurry of diplomatic activity. But the core dynamic is already set. China has put a price on its mineral dominance, and the invoice is due at the end of the quarter. The only question is whether Washington is willing—or even able—to pay it.

The Invoice is Dated December 1st

Let's be clear. The "national security" justification is diplomatic window dressing for a masterclass in economic hardball. For decades, the West offshored its industrial base and complex refining processes in the pursuit of efficiency, creating critical single-point-of-failure dependencies. We are now seeing the strategic cost of that decision. China isn't creating a new vulnerability; it is simply exploiting a pre-existing one that the U.S. and its allies chose to ignore. This isn't an act of aggression. It's an act of leverage, applied with the precision of a surgeon. The December 1st deadline isn't a threat; it's the due date on an invoice for twenty years of supply chain complacency.

-

The Business of Plasma Donation: How the Process Works and Who the Key Players Are

Theterm"plasma"suffersfromas...

-

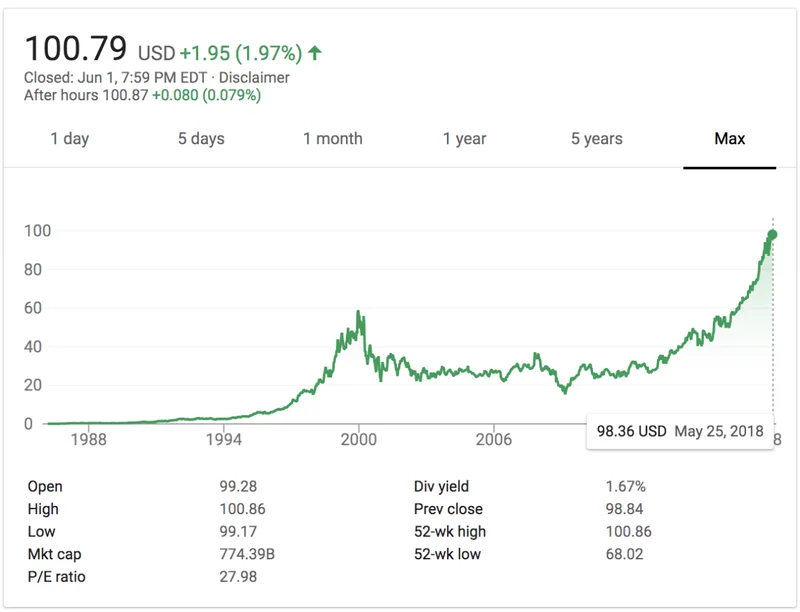

ASML's Future: The 2026 Vision and Why Its Next Breakthrough Changes Everything

ASMLIsn'tJustaStock,It'sthe...

-

Morgan Stanley's Q3 Earnings Beat: What This Signals for Tech & the Future of Investing

It’seasytoglanceataheadline...

-

The Manyu Phenomenon: What Connects the Viral Crypto, the Tennis Star, and the Anime Legend

It’seasytodismisssportsasmer...

-

The Nebius AI Breakthrough: Why This Changes Everything

It’snotoftenthatatypo—oratl...

- Search

- Recently Published

-

- Misleading Billions: The Truth About DeFi TVL - DeFi Reacts

- Secure Crypto: Unlock True Ownership - Reddit's HODL Guide

- Altcoin Season is "here.": What's *really* fueling the latest altcoin hype (and who benefits)?

- The Week's Pivotal Blockchain Moments: Unpacking the breakthroughs and their visionary future

- DeFi Token Performance Post-October Crash: What *actual* investors are doing and the brutal 2025 forecast

- Monad: A Deep Dive into its Potential and Price Trajectory – What Reddit is Saying

- MSTR Stock: Is This Bitcoin's Future on the Public Market?

- OpenAI News Today: Their 'Breakthroughs' vs. The Broken Reality

- Medicare 2026 Premium Surge: What We Know and Why It Matters

- Accenture: What it *really* is, its stock, and the AI game – What Reddit is Saying

- Tag list

-

- Blockchain (11)

- Decentralization (5)

- Smart Contracts (4)

- Cryptocurrency (26)

- DeFi (5)

- Bitcoin (30)

- Trump (5)

- Ethereum (8)

- Pudgy Penguins (5)

- NFT (5)

- Solana (5)

- cryptocurrency (6)

- XRP (3)

- Airdrop (3)

- MicroStrategy (3)

- Plasma (4)

- Zcash (7)

- Aster (10)

- qs stock (3)

- mstr stock (3)

- asts stock (3)

- investment advisor (4)

- morgan stanley (3)

- ChainOpera AI (4)

- federal reserve news today (4)