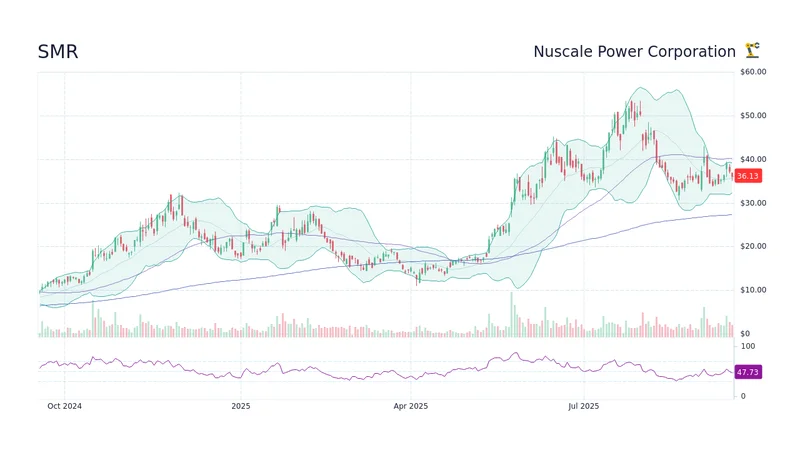

NuScale Power (SMR) Stock: What the Data Says About Its Future

The search queries tell a story. "Is SMR a good stock to buy?" "What is the best SMR stock?" "Who is the leader in SMR technology?" You can almost feel the collective hum of retail investor interest, a kind of digital gold rush for the next great energy revolution. The narrative is powerful, almost intoxicating: Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) are the future—clean, safe, scalable nuclear power that will solve the climate crisis and generate massive returns for early believers.

But when I look at the SMR sector, I don’t see a clear investment thesis. I see a venture capital portfolio masquerading as a publicly traded industry. The questions people are asking are fundamentally flawed because they presuppose a reality that doesn't exist yet. We're not comparing established companies based on price-to-earnings ratios or discounted cash flow. We're evaluating blueprints, regulatory applications, and corporate promises. Asking for the "best" SMR stock today is like asking for the "best" commercial airline in 1904. The Wright brothers have a promising prototype, but the airport, the supply chain, and the paying customers are all still decades away.

The real task for a sober analyst isn't to pick a winner from a field of contenders who haven't even started the race. It's to measure the staggering distance between the starting line and the finish.

The Anatomy of a Pre-Revenue Industry

Let’s be precise about what we’re looking at. The vast majority of publicly accessible SMR companies are, for all intents and purposes, pre-revenue. Their financial statements are a chronicle of cash burn, funded by equity raises and government grants. Their primary products are not megawatts of electricity, but press releases announcing memorandums of understanding (MOUs) and successful simulation results.

This isn't a criticism; it's a classification. It places these companies in a specific high-risk, high-reward category. An investment here is a bet on three monumental hurdles: technological viability at scale, regulatory approval, and economic competitiveness. The current hype cycle seems to focus almost exclusively on the first, while underestimating the other two.

Think of it like this: An SMR company is not a utility. A utility has predictable cash flows and a regulated monopoly. An SMR company is a biotech firm trying to get a blockbuster drug through FDA trials. It has a compelling scientific hypothesis, a team of brilliant engineers, and a long, expensive, and uncertain path to commercialization. Many will fail. A few might succeed spectacularly, but only after burning through mountains of capital and navigating a bureaucratic maze that makes the FDA look simple. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) is not known for its speed or leniency, and for good reason. The first company to get a design fully certified and built will be a landmark achievement, but the timeline is anyone's guess.

I've looked at hundreds of these filings, and this particular sector is unique in its reliance on projections that extend ten, even fifteen years into the future. We see charts forecasting hockey-stick revenue growth starting in, say, 2032. The problem? The assumptions underpinning those charts are heroic. They assume NRC approval on a specific schedule, construction costs that stay within budget (a rarity in the nuclear world), and a future energy market where their levelized cost of electricity is competitive. A delay of two years or a cost overrun of about 20%—to be more exact, a 22% overrun based on historical nuclear projects—could completely invalidate the entire model.

Measuring the Unmeasurable

So, if we can't use traditional metrics, what can we look at? Investors are left grasping at qualitative signals. Who has the most government funding? Who has the most impressive list of potential partners? Which design seems the most plausible on paper? This is where the analysis breaks down, because these are not hard data points.

Government funding (often from the Department of Energy) is certainly a vote of confidence, but it’s not a guarantee of commercial success. It’s seed capital designed to de-risk the technology, not an endorsement of a specific company's business model. The MOUs are even softer data. An agreement to "explore the possibility" of building a reactor in a specific country is not a firm purchase order. It’s a letter of intent, and the path from intent to a signed, multi-billion-dollar construction contract is treacherous.

The central discrepancy is between the story and the balance sheet. The story is about revolutionizing global energy. The balance sheet is about R&D expenses and shareholder dilution. And this is the part of the sector that I find genuinely puzzling: the market's willingness to assign multi-billion-dollar valuations to companies whose primary asset is intellectual property that has yet to be commercially validated. NuScale Power, often held up as the American frontrunner, holds the only NRC design certification, a major milestone. Yet even they saw their first planned project with Utah Associated Municipal Power Systems (UAMPS) cancelled due to rising cost estimates (the projected price rose by a staggering 75%).

This isn't a failure of the technology itself. It's a brutal collision with economic reality. It demonstrates that even with regulatory progress, the numbers still have to work. What does that tell us about the dozens of other companies that are years behind NuScale in the regulatory queue? What are their real, risk-adjusted prospects? These are the questions that get lost in the excitement over technical specifications and animated reactor diagrams.

The Real Metric is Execution, Not Design

The search for a technological "leader" is a red herring. It’s possible, even likely, that several SMR designs will prove technologically sound. The winner of this race won't necessarily be the company with the most elegant physics or the highest thermal efficiency. The winner will be the company that demonstrates an almost fanatical discipline in project management, supply chain logistics, and regulatory navigation.

The ultimate test for any SMR company isn't the lab; it's the first concrete pour. It will be the first to build a reactor on time and on budget, proving that the "modular" concept can actually deliver the promised cost savings at scale. Until a company does that, we are all just speculating. We're betting on management teams, on engineering blueprints, and on the hope that this time, the nuclear industry can break its decades-long habit of over-promising and under-delivering on cost and schedule.

So, when you ask who the leader is, you're asking the wrong question. The right question is: Who is most likely to be the first to turn a computer-aided design into a functioning, grid-connected, and economically viable power plant? The honest answer, based on the publicly available data, is that it's far too early to tell. Investing now is an act of faith in a very long-term, high-risk proposition. The data simply isn't there to make it anything else.

-

The Business of Plasma Donation: How the Process Works and Who the Key Players Are

Theterm"plasma"suffersfromas...

-

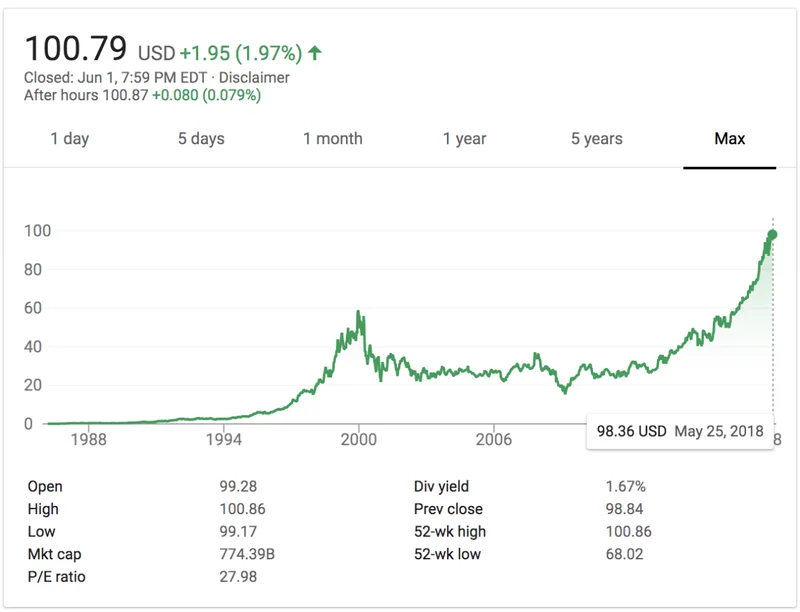

ASML's Future: The 2026 Vision and Why Its Next Breakthrough Changes Everything

ASMLIsn'tJustaStock,It'sthe...

-

Morgan Stanley's Q3 Earnings Beat: What This Signals for Tech & the Future of Investing

It’seasytoglanceataheadline...

-

The Manyu Phenomenon: What Connects the Viral Crypto, the Tennis Star, and the Anime Legend

It’seasytodismisssportsasmer...

-

The Nebius AI Breakthrough: Why This Changes Everything

It’snotoftenthatatypo—oratl...

- Search

- Recently Published

-

- Misleading Billions: The Truth About DeFi TVL - DeFi Reacts

- Secure Crypto: Unlock True Ownership - Reddit's HODL Guide

- Altcoin Season is "here.": What's *really* fueling the latest altcoin hype (and who benefits)?

- The Week's Pivotal Blockchain Moments: Unpacking the breakthroughs and their visionary future

- DeFi Token Performance Post-October Crash: What *actual* investors are doing and the brutal 2025 forecast

- Monad: A Deep Dive into its Potential and Price Trajectory – What Reddit is Saying

- MSTR Stock: Is This Bitcoin's Future on the Public Market?

- OpenAI News Today: Their 'Breakthroughs' vs. The Broken Reality

- Medicare 2026 Premium Surge: What We Know and Why It Matters

- Accenture: What it *really* is, its stock, and the AI game – What Reddit is Saying

- Tag list

-

- Blockchain (11)

- Decentralization (5)

- Smart Contracts (4)

- Cryptocurrency (26)

- DeFi (5)

- Bitcoin (30)

- Trump (5)

- Ethereum (8)

- Pudgy Penguins (5)

- NFT (5)

- Solana (5)

- cryptocurrency (6)

- XRP (3)

- Airdrop (3)

- MicroStrategy (3)

- Plasma (4)

- Zcash (7)

- Aster (10)

- qs stock (3)

- mstr stock (3)

- asts stock (3)

- investment advisor (4)

- morgan stanley (3)

- ChainOpera AI (4)

- federal reserve news today (4)