The American Middle Class: Redefining the Term and the Data Behind the 'Squeeze'

Here is the feature article, written from the persona of Julian Vance.

*

# The New Squeeze on the Middle Class Is Hiding Behind a Paywall

The question hangs in the digital ether, stark and provocative: "Are we earning enough? The new squeeze on the middle classes." It's the headline of a recent Financial Times piece, and it’s arguably one of the most critical macroeconomic and personal finance questions of our era. It speaks to a quiet, persistent anxiety humming beneath the surface of Western economies—the feeling of running faster just to stay in the same place.

So, what’s the answer? What data-driven insights has the FT uncovered about this phenomenon?

I can’t tell you.

When you attempt to access the analysis, you don’t get a chart or a paragraph. You get a subscription page. The diagnosis for the defining economic condition of our time is a premium product. The quiet hum of my office server was broken by the click of my mouse, and there it was: a digital tollbooth erected on the very road that promises to explain why you can’t afford all the other tolls.

And this, right here, is the only data point we really need. The FT’s paywall is a more elegant and damning piece of evidence for the middle-class squeeze than any article it obscures. The medium isn't just the message; it's the conclusion.

The Signal in the Noise

In my former life on a trading desk, the most valuable commodity wasn't capital; it was information asymmetry. You paid dearly for an edge, for a piece of analysis or a data feed that others didn't have. That model makes sense in a zero-sum game of market speculation. But it's a deeply corrosive model when applied to fundamental societal questions.

What we're seeing is the "premium-ization" of economic self-awareness. The analysis of widespread financial precarity is being packaged and sold as a luxury good. It's like a team of epidemiologists conducting a city-wide study on a new public health threat, only to then sell the report exclusively to the wealthiest citizens, who can afford to act on its findings. The very people who are the subject of the study—those most at risk—are the ones firewalled from the information.

This isn't an accident; it's a business model. And it forces us to ask some uncomfortable questions. What does it say about our economic discourse when the diagnosis costs more than many can spare? Is financial literacy, the supposed bedrock of personal responsibility, now a subscription service? I've looked at hundreds of these economic reports over the years, and the trend of gating foundational knowledge is accelerating. It's a subtle shift from journalism as a public service to journalism as a private intelligence briefing for a select clientele.

The irony is so potent it's almost poetic. The system is monetizing the very anxiety it creates.

The Data We Can See

While the FT’s specific analysis remains locked away, the broader metrics are available to anyone willing to look. We don't need a subscription to know that for decades, the cost of the core pillars of a middle-class life—housing, education, and healthcare—has dramatically outpaced wage growth.

For the last fifteen years, real wages have been largely flat—or to be more exact, for the median worker, they've risen just a fraction of a percent above inflation annually, creating a treadmill effect where any perceived gain is immediately consumed by rising costs. The cost of a four-year college degree, for instance, has outstripped the Consumer Price Index by a staggering amount (some indices put it at over 150% in the last 20 years). A home, once the anchor of middle-class wealth, is now an impossibly distant goal for millions.

These aren't controversial data points. They are the ambient facts of our economic reality. The value of an article like the FT's isn't in revealing these trends, but in synthesizing them into a coherent narrative. It offers to transform a vague, personal sense of unease into a well-defined, systemic phenomenon. It tells you you're not crazy. It confirms your struggle is not a unique personal failing but a shared condition.

And that is a powerful product to sell. It provides intellectual comfort, a sense of clarity in the fog of economic uncertainty. The target audience, the family `stuck in the middle` of these crushing forces, is ironically the least likely to have the disposable income for a subscription that explains their own predicament. Who, then, is the article for? Is it for the squeezed, or is it for the investors and policymakers who watch them from a comfortable and analytical distance?

Extrapolating the Silence

Without seeing the text, we are forced to speculate on its contents. It’s a useful exercise. The piece likely details the hollowing out of the center of the economy. It probably contains well-researched vignettes of families who, despite having advanced degrees and stable jobs, find themselves unable to save, invest, or provide a better life for their children than their parents did. It almost certainly discusses the bifurcation of the labor market into a high-skill, high-wage professional class and a low-wage service class, with the paths between the two becoming ever more narrow.

The core issue is that being `in the middle` no longer implies stability; it implies exposure. You are exposed to downside risk from healthcare emergencies and job losses, yet you are largely excluded from the upside gains of asset appreciation that disproportionately benefit the top 10%. You have the obligations of the wealthy (taxes, college tuition) but the financial fragility of the working class.

The most profound "squeeze" may not even be financial, but psychological. It's the cognitive dissonance of following all the rules of the 20th-century playbook for success—get an education, work hard, buy a home—only to find that the game has fundamentally changed. The rules are different, the goalposts have moved, and the referee is charging you a fee to read the new rulebook. What is the long-term effect of a society where a significant portion of the population feels like they are, to borrow a title from a different era, `Malcolm in the Middle` of an economic joke they don't get?

The Price of the Answer is the Answer

Let's be perfectly clear. The Financial Times is a premier publication, and I have no doubt the analysis behind their paywall is rigorous and insightful. They have every right to charge for their work. But that is a separate issue.

The real story here is the meta-narrative. The question "Are we earning enough?" is answered the moment you are asked to pay for the article. For a growing and significant portion of the population, the answer is a resounding "no." They aren't earning enough to build savings, to afford the markers of a stable life, or even, in this case, to afford the very analysis that would confirm their own economic reality. The existence of the question as a premium product is the only answer that matters. It validates the premise completely. The squeeze isn't a theory to be debated; it's a reality demonstrated by the simple act of a paywall.

-

The Business of Plasma Donation: How the Process Works and Who the Key Players Are

Theterm"plasma"suffersfromas...

-

ASML's Future: The 2026 Vision and Why Its Next Breakthrough Changes Everything

ASMLIsn'tJustaStock,It'sthe...

-

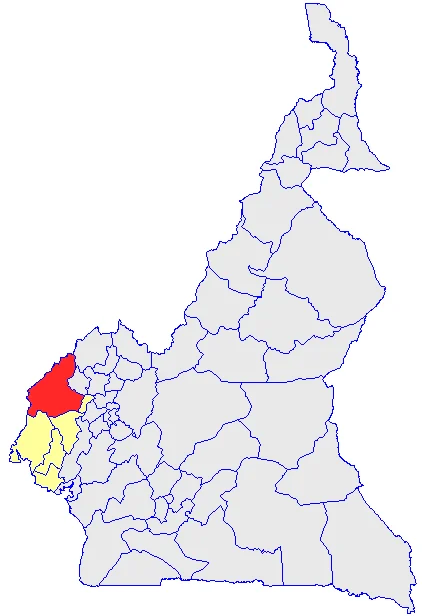

The Manyu Phenomenon: What Connects the Viral Crypto, the Tennis Star, and the Anime Legend

It’seasytodismisssportsasmer...

-

The Nebius AI Breakthrough: Why This Changes Everything

It’snotoftenthatatypo—oratl...

-

Secure Crypto: Unlock True Ownership - Reddit's HODL Guide

Alright,folks,let'stalkcrypto....

- Search

- Recently Published

-

- Misleading Billions: The Truth About DeFi TVL - DeFi Reacts

- Secure Crypto: Unlock True Ownership - Reddit's HODL Guide

- Altcoin Season is "here.": What's *really* fueling the latest altcoin hype (and who benefits)?

- The Week's Pivotal Blockchain Moments: Unpacking the breakthroughs and their visionary future

- DeFi Token Performance Post-October Crash: What *actual* investors are doing and the brutal 2025 forecast

- Monad: A Deep Dive into its Potential and Price Trajectory – What Reddit is Saying

- MSTR Stock: Is This Bitcoin's Future on the Public Market?

- OpenAI News Today: Their 'Breakthroughs' vs. The Broken Reality

- Medicare 2026 Premium Surge: What We Know and Why It Matters

- Accenture: What it *really* is, its stock, and the AI game – What Reddit is Saying

- Tag list

-

- Blockchain (11)

- Decentralization (5)

- Smart Contracts (4)

- Cryptocurrency (26)

- DeFi (5)

- Bitcoin (30)

- Trump (5)

- Ethereum (8)

- Pudgy Penguins (5)

- NFT (5)

- Solana (5)

- cryptocurrency (6)

- XRP (3)

- Airdrop (3)

- MicroStrategy (3)

- Plasma (4)

- Zcash (7)

- Aster (10)

- qs stock (3)

- mstr stock (3)

- asts stock (3)

- investment advisor (4)

- morgan stanley (3)

- ChainOpera AI (4)

- federal reserve news today (4)