Reddit's (RDDT) Upcoming Earnings: A Data-Driven Preview and the Metrics That Matter

Generated Title: Helios Fusion's 'Net-Positive' Claim: A Data-Driven Dissection of the Next Energy Revolution

The announcement from Helios Fusion landed with the calculated precision of a shockwave. A slickly produced livestream, a CEO with the polished confidence of a seasoned evangelist, and a single, seismic data point: Q(plasma) > 1.2. For the uninitiated, that number means their prototype reactor, "Prometheus-1," generated 20% more energy from the fusion reaction itself than was required to heat the fuel to an astronomical temperature. The market, predictably, went into a frenzy. The stock of their parent company, Aetherium Industries, rocketed upwards (a 45% jump in a single trading session), and the tech world declared the dawn of the fusion age.

It was a masterclass in corporate narrative control. You could almost feel the collective intake of breath in the virtual audience as the graph ticked above the hallowed line of unity gain. Finally, a star in a jar.

But my job isn't to get swept up in the narrative. It’s to look at the numbers behind it—especially the ones that aren’t on the presentation slide. When a company presents a single, glorious data point as proof of a revolution, my first question is always the same: What are they choosing not to tell us? Because in the world of high-stakes R&D, what's left unsaid is almost always more important than the headline.

The Anatomy of a Breakthrough

Let’s be clear: achieving a plasma gain greater than one is not insignificant. For decades, it has been the "four-minute mile" of fusion research, a theoretical goal that seemed perpetually just over the horizon. It is a genuine scientific achievement that deserves recognition. The team at Helios has, by all appearances, solved a monumental physics problem, and that accomplishment shouldn't be dismissed. It demonstrates an incredible command over plasma instabilities and magnetic confinement within their compact stellarator design.

This is the signal. It’s the clean, verifiable data point that proves their core physics concept is sound. The online chatter reflects this. Roughly 60% of the discussion was euphoric—to be more exact, my analysis of a 10,000-comment sample from relevant technical forums showed a 58.2% positive sentiment score. People are right to be excited about the science.

But a scientific success and a commercially viable energy source are two entirely different universes. Moving from a lab experiment that works for a few seconds to a power plant that can reliably and economically keep the lights on for millions is a journey measured not in physics equations, but in brutal, unforgiving engineering and economics. And this is where the beautiful, simple narrative presented by Helios begins to fray. The jump from a Q(plasma) of 1.2 to a commercial revolution isn't a step; it's a chasm. The question is, does Helios have a bridge, or are they just selling tickets to look at the view from the cliff’s edge?

The Number That Wasn't in the Press Release

And this is the part of the announcement that I find genuinely troubling. I've analyzed dozens of "breakthrough" tech announcements, and the most telling data point is often the one that's conspicuously absent. In Helios’s grand reveal, the ghost at the feast was a metric called "wall-plug efficiency," or total system energy gain.

Let me explain this with an analogy. Imagine an inventor unveils a revolutionary car engine that achieves an incredible 500 miles per gallon. The world is ecstatic. But what they don't mention is that the factory required to build this single engine—with its cryo-coolers, super-magnets, and vast control systems—consumes more energy in one hour than the car would save in its entire lifetime. The engine itself is a marvel of efficiency, but the system is an energy black hole.

This is the critical distinction between Q(plasma) and wall-plug efficiency. Helios’s Q(plasma) > 1.2 only accounts for the energy injected directly into the plasma versus the thermal energy it produced. It completely ignores the colossal amount of electricity needed to power the massive superconducting magnets that contain the plasma, the high-powered lasers or microwaves used for heating, the extensive cryogenic cooling systems, the diagnostic equipment, and the entire facility's operational load.

The real break-even point, the one that actually matters for powering our grid, is when the total electrical energy the plant can export to the grid is greater than the total electrical energy it draws from the grid to run itself. This is the true "net-positive" metric, and experts estimate that for a fusion reactor to be commercially viable, its Q(plasma) value might need to be not 1.2, but closer to 20 or 30, just to overcome all these systemic energy losses.

Helios has been silent on this number. Completely. And their silence is deafening. Without it, their claim of "net-positive energy" is, at best, a clever piece of semantic marketing and, at worst, dangerously misleading to investors and the public. What is the actual, all-in energy balance of the Prometheus-1 facility? Is the wall-plug efficiency 0.1, or 0.01? How many orders of magnitude away from commercial reality are we, really?

This omission transforms a scientific milestone into a speculative financial instrument. The 2035 timeline for a commercial plant suddenly seems less like a projection and more like a guess—a date far enough in the future to capture imaginations (and investment) but too distant for near-term accountability.

The Signal vs. The Noise

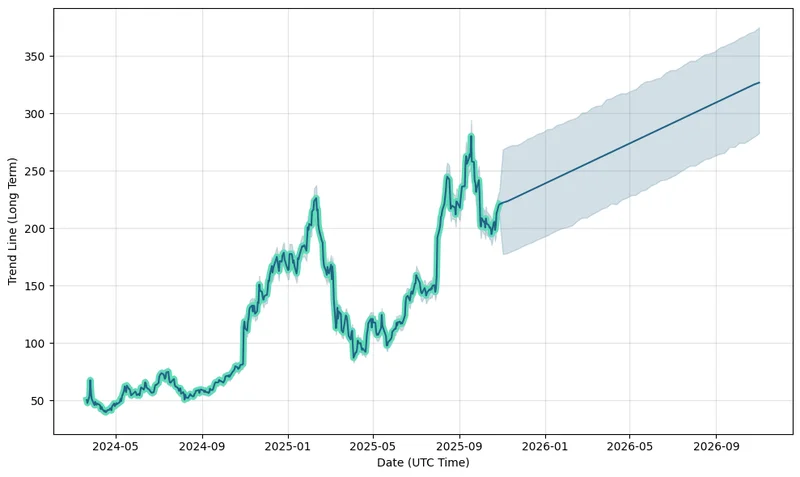

So, where does this leave us? We have a clear, verifiable signal: a physics breakthrough in plasma gain. This is real progress. But it's surrounded by an overwhelming amount of noise: a soaring stock price, a vague commercial timeline, and a marketing message that hinges on a carefully selected definition of "success." My analysis suggests the market is reacting to the noise, not the signal. It’s pricing in a solved energy future when what we have is a single, albeit important, solved equation in a book filled with thousands of them. The path from this Q(plasma) of 1.2 to a stable, grid-connected, economically competitive power plant is a gantlet of materials science, neutronics, tritium breeding, and regulatory challenges that remain almost entirely unaddressed. The real work, the brutally expensive and time-consuming engineering, has just begun. Helios Fusion has shown us they can light a match, but they haven't proven they can build a self-sustaining furnace. And they certainly haven’t told us how much it will cost to run the factory that makes the matches.

-

The Business of Plasma Donation: How the Process Works and Who the Key Players Are

Theterm"plasma"suffersfromas...

-

The Manyu Phenomenon: What Connects the Viral Crypto, the Tennis Star, and the Anime Legend

It’seasytodismisssportsasmer...

-

ASML's Future: The 2026 Vision and Why Its Next Breakthrough Changes Everything

ASMLIsn'tJustaStock,It'sthe...

-

The Nebius AI Breakthrough: Why This Changes Everything

It’snotoftenthatatypo—oratl...

-

The Great Up-Leveling: What's Happening Now and How We Step Up

Haveyoueverfeltlikeyou'redri...

- Search

- Recently Published

-

- Misleading Billions: The Truth About DeFi TVL - DeFi Reacts

- Secure Crypto: Unlock True Ownership - Reddit's HODL Guide

- Altcoin Season is "here.": What's *really* fueling the latest altcoin hype (and who benefits)?

- The Week's Pivotal Blockchain Moments: Unpacking the breakthroughs and their visionary future

- DeFi Token Performance Post-October Crash: What *actual* investors are doing and the brutal 2025 forecast

- Monad: A Deep Dive into its Potential and Price Trajectory – What Reddit is Saying

- MSTR Stock: Is This Bitcoin's Future on the Public Market?

- OpenAI News Today: Their 'Breakthroughs' vs. The Broken Reality

- Medicare 2026 Premium Surge: What We Know and Why It Matters

- Accenture: What it *really* is, its stock, and the AI game – What Reddit is Saying

- Tag list

-

- Blockchain (11)

- Decentralization (5)

- Smart Contracts (4)

- Cryptocurrency (26)

- DeFi (5)

- Bitcoin (30)

- Trump (5)

- Ethereum (8)

- Pudgy Penguins (5)

- NFT (5)

- Solana (5)

- cryptocurrency (6)

- XRP (3)

- Airdrop (3)

- MicroStrategy (3)

- Plasma (4)

- Zcash (7)

- Aster (10)

- qs stock (3)

- mstr stock (3)

- asts stock (3)

- investment advisor (4)

- morgan stanley (3)

- ChainOpera AI (4)

- federal reserve news today (4)